Electric car future may depend on deep sea mining

The future of electric cars may depend on mining critically important metals on the ocean floor.

That’s the view of the engineer leading a major European investigation into new sources of key elements.

Demand is soaring for the metal cobalt – an essential ingredient in batteries and abundant in rocks on the seabed.

Laurens de Jonge, who’s running the EU project, says the transition to electric cars means “we need those resources”.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

He was speaking during a unique set of underwater experiments designed to assess the impact of extracting rocks from the ocean floor.

In calm waters 15km off the coast of Malaga in southern Spain, a prototype mining machine was lowered to the seabed and ‘driven’ by remote control.

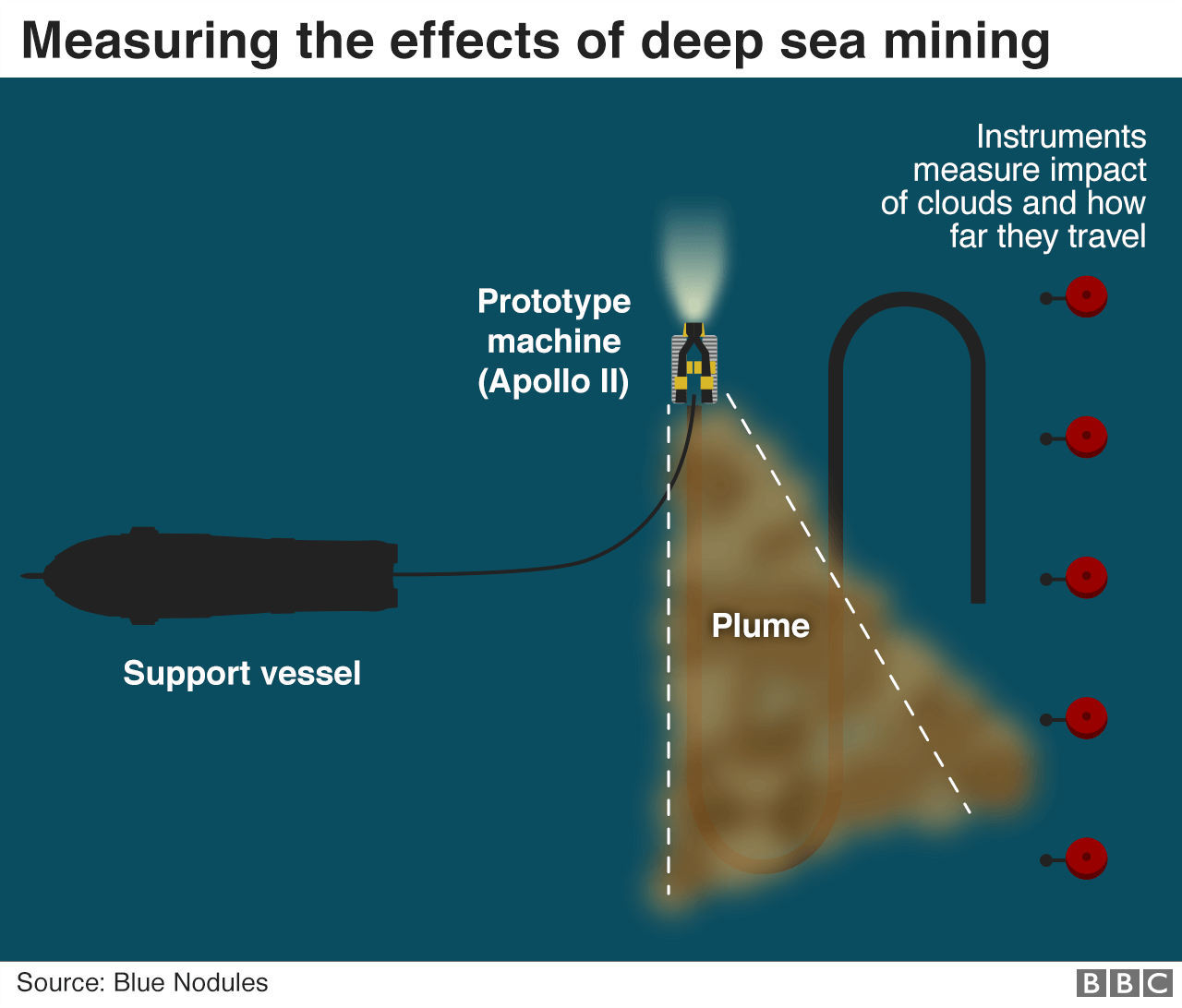

Cameras attached to the Apollo II machine recorded its progress and, crucially, monitored how the aluminium tracks stirred up clouds of sand and silt as they advanced.

Did deep sea mining start with CIA plot?

An array of instruments was positioned nearby to measure how far these clouds were carried on the currents – the risk of seabed mining smothering marine life over a wide area is one of the biggest concerns.

What is ‘deep sea mining’?

It’s hard to visualise, but imagine opencast mining taking place at the bottom of the ocean, where huge remote-controlled machines would excavate rocks from the seabed and pump them up to the surface.

The concept has been talked about for decades, but until now it’s been thought too difficult to operate in the high-pressure, pitch-black conditions as much as 5km deep.

Now the technology is advancing to the point where dozens of government and private ventures are weighing up the potential for mines on the ocean floor.

Why would anyone bother?

The short answer: demand. The rocks of the seabed are far richer in valuable metals than those on land and there’s a growing clamour to get at them.

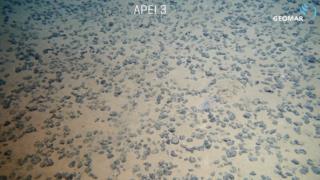

Billions of potato-sized rocks known as “nodules” litter the abyssal plains of the Pacific and other oceans and many are brimming with cobalt, suddenly highly sought after as the boom in the production of batteries gathers pace.

At the moment, most of the world’s cobalt is mined in the Democratic Republic of Congo where for years there’ve been allegations of child labour, environmental damage and widespread corruption.

Image copyright

Getty Images

Expanding production there is not straightforward which is leading mining companies to weigh the potential advantages of cobalt on the seabed.

Laurens de Jonge, who’s in charge of the EU project, known as Blue Nodules, said: “It’s not difficult to access – you don’t have to go deep into tropical forests or deep into mines.

“It’s readily available on the seafloor, it’s almost like potato harvesting only 5km deep in the ocean.”

And he says society faces a choice: there may in future be alternative ways of making batteries for electric cars – and some manufacturers are exploring them – but current technology requires cobalt.

Image copyright

Geomar

“If you want to make a fast change, you need cobalt quick and you need a lot of it – if you want to make a lot of batteries you need the resources to do that.”

His view is backed by a group of leading scientists at London’s Natural History Museum and other institutions.

They recently calculated that meeting the UK’s targets for electric cars by 2050 would require nearly twice the world’s current output of cobalt.

So what are the risks?

No one can be entirely sure, which makes the research off Spain highly relevant.

It’s widely accepted that whatever is in the path of the mining machines will be destroyed – there’s no argument about that.

But what’s uncertain is how far the damage will reach, in particular the size of the plumes of silt and sand churned up and the distance they will travel, potentially endangering marine life far beyond the mining site.

The chief scientist on board, Henko de Stigter of the Dutch marine research institute NIOZ, points out that life in the deep Pacific – where mining is likely to start first – has adapted to the usually “crystal clear conditions”.

So for any organisms feeding by filter, waters that are suddenly filled with stirred-up sediment would be threatening.

“Many species are unknown or not described, and let alone do we know how they will respond to this activity – we can only estimate.”

And Dr de Stigter warned of the danger of doing to the oceans what humanity has done to the land.

“With every new human activity it’s often difficult to foresee all the consequences of that in the long term.

“What is new here is that we are entering an environment that is almost completely untouched.”

Could deep sea mining be made less damaging?

Ralf Langeler thinks so. He’s the engineer in charge of the Apollo II mining machine and he believes the design will minimise any impacts.

Like Laurens de Jonge, he works for the Dutch marine engineering giant Royal IHC and he says his technology can help reduce the environmental effects.

The machine is meant to cut a very shallow slice into the top 6-10cm of the seabed, lifting the nodules. Its tracks are made with lightweight aluminium to avoid sinking too far into the surface.

Silt and sand stirred up by the extraction process should then be channelled into special vents at the rear of the machine and released in a narrow stream, to try to avoid the plume spreading too far.

“We’ll always change the environment, that’s for sure,” Ralf says, “but that’s the same with onshore mining and our purpose is to minimise the impact.”

I ask him if deep sea mining is now a realistic prospect.

“One day it’s going to happen, especially with the rising demand for special metals – and they’re there on the sea floor.”

Who decides if it goes ahead?

Mining in territorial waters can be approved by an individual government.

That happened a decade ago when Papua New Guinea gave the go-ahead to a Canadian company, Nautilus Minerals, to mine gold and copper from hydrothermal vents in the Bismarck Sea.

Since then the project has been repeatedly delayed as the company ran short of funds and the prime minister of PNG called for a 10-year moratorium on deep sea mining.

A Nautilus Minerals representative has told me that the company is being restructured and that they remain hopeful of starting to mine.

Meanwhile, nearly 30 other ventures are eyeing areas of ocean floor beyond national waters, and these are regulated by a UN body, the International Seabed Authority (ISA).

It has issued licences for exploration and is due next year to publish the rules that would govern future mining.

The EU’s Blue Nodules project involves a host of different institutions and countries.

The vessel used for the underwater research off Spain, the Sarmiento de Gamboa, is operated by CSIC, the Spanish National Research Council.

Follow David on Twitter.

0 comments